Dr Rachel E. Phillips | A.G. Leventis Fellow in Hellenic Studies

March shines a spotlight on Women’s History worldwide. In this blog, we are excited to feature an international contributor, Rachel Phillips, from the British School at Athens. Rachel offers us insight into an archival project that looks at the experiences of women at the British School at Athens between 1890 and 1920.

Background

Women can be hard to locate in archival records. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women’s roles and activities were overlooked by their academic institutions—and often their personal papers do not survive. But some details about women’s experiences can be reconstructed from the close examination of these records, even if from the perspective of the institution rather than from the perspective of the women themselves.

At the start of the twentieth century, women were often denied access to the funds and resources of British universities. However, at the British School at Athens, founded in 1886 as an institute for archaeological research in Greece, women played an important role early in its history. Female researchers came out to Greece to continue their studies, and were able to access the books and resources of the institution.

They were not permitted to stay at the BSA hostel with the male students, however, and unlike their male counterparts, they were not considered for funded positions. They were accepted as members of the School only if they could fund their own residence in Greece. Christina Mackenzie, for example, the sister of Duncan Mackenzie who later excavated at Knossos, was refused funds from the School in 1897 and so was unable to travel to Greece.

In this post, I explore one pivotal episode in this story—the debate around the admission of women to funded positions at the BSA, reconstructed via records held in the School archives.

Jobs for women?

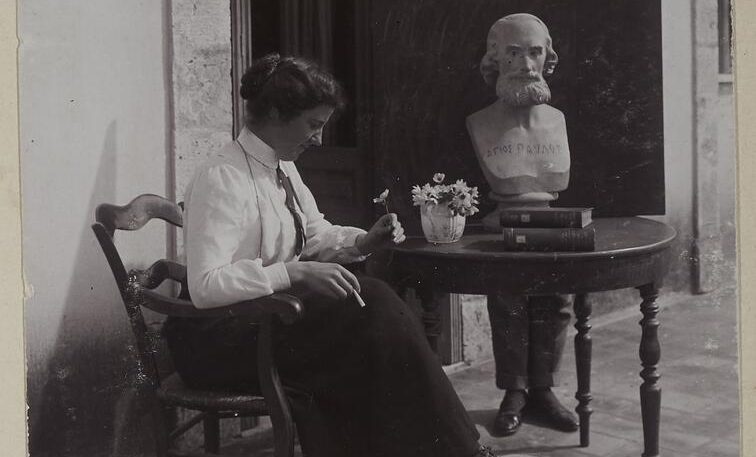

The first woman to receive a funded position at the BSA was Margaret Hardie in 1911, twenty-five years after the foundation of the School. Hardie came to the BSA to continue her studies in Classics: in her role as School Student, she published on the site of Antioch in Pisidia, where she had excavated in the summer of 1911.

She was nominated for the studentship (the conventional term for these funded positions) by the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, after a recommendation from Jane Harrison, a Classics scholar at Newnham College. The BSA committee accepted Hardie for the position—they could hardly refuse the Vice-Chancellor—but its members later raised a motion to disbar women from future funded positions at the School.

Letter from the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge to the BSA Secretary John Baker Penoyre, on 17 June 1911, nominating Margaret Hardie for the studentship (BSA Corporate Records: London). Fair Use under Section 30 of the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The committee intervenes…

This motion resulted in an extended debate between the Committee on the one side and Jane Harrison on the other side, preserved in the BSA Corporate Records. In a letter to the Committee on 17 August 1912, Harrison writes an impassioned defence of the role of women at the BSA, and sets out her arguments in favour of studentships for women.

“The recent action of the Committee”—she says—“has distressed and perplexed me. I venture to think that after long pondering I see the explanation of it in a possible confusion of two issues. 1. The question of whether women are to be School Students. 2. Whether women are to be present at excavations.”

The Excavation Question

The BSA studentships had always involved participation in Greek excavations, at least for the male students. But the place of women on excavations was a contested issue at the time: Richard Dawkins, the Director of the BSA from 1906 to 1914, recorded his discomfort with women on excavations in letters to the BSA Secretary between 1910 and 1911, where he states that their presence disrupted the male camaraderie.

For Harrison, however, the question of female participation in excavations was a separate issue to the question of female studentships. She also raised the important point that it was mostly women who funded the BSA studentships, in their roles as members and subscribers. The question of female studentships, for Harrison, should therefore be put before the subscribers rather than the Committee.

The debate concludes…

The outcome of the debate is recorded in the Minutes of the 1913 Annual Meeting: the Committee accorded preference to male candidates but would admit women in cases where there were no suitable men. In technical terms, Harrison had won the debate—women could officially be admitted to BSA studentships, at the expense of their involvement in excavations.

But in practical terms, this decision effectively excluded women from funded positions at the BSA. The Committee’s actions were mediated by the efforts of Jane Harrison but the outcome nonetheless made it more difficult for women to study at the School. The next woman to receive a studentship is Lilian Chandler in 1920—almost a decade later.

© British School at Athens.

At the BSA today

These early female students at the BSA paved the way for later pioneers of Greek archaeological work. Renowned epigraphist Anne Jeffery and Near Eastern archaeologist Vronwy Hankey (née Fisher), for example, both received funded studentships from the BSA in the 1930s.

Today, the BSA is run by its third female director, Professor Rebecca Sweetman. Over 100 years later, the School can celebrate the contribution of these women to the field in spite of the institutional barriers that they faced.

Further Information

- British School at Athens

- BSA Instagram

- BSA Facebook

- Bluesky account: @britschoolathens.bsky.social

- Dr. Rachel Phillips’ BSA profile

Written by Dr Rachel E. Phillips, A.G. Leventis Fellow in Hellenic Studies (British School at Athens)

Coordinated by Anya Hopkins (Blog Coordinator, Explore Your Archive)