January’s Explore Your Archive in-theme blog explores the idea of ‘dustbusting’.

In popular consciousness archives are like vast hallowed halls or secret warehouses lined and filled with stacks of old manuscripts and books, some tattily-bound and moldering away over the centuries, in varying states of preservation – and just possibly, interspersed among them, a few classified treasures (think Raiders of the Lost Ark).

But what are archives really like? Archivist Tom Plant and Conservator Sophie Coles invite us in. From the Wiltshire & Swindon Heritage Centre they cast open the doors of the ‘dusty old archives’.

The ‘dusty old archives’…

Few images seem to be as popularly enduring as that of the ‘dusty old archives’. It appears in all forms of media, even blockbuster films. In The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf rummages through teetering stacks of disorganised papers in Gondor’s archive (in the cellars, naturally), armed with a flaming torch, his pipe, and a quill pen for good measure.

There seems to be something very powerful about the idea that archives are dirty and untidy piles of material, slowly mouldering away in storage.

Certainly, some collections first arrive in the archive in a sorry state. Sometimes they have been kept in attics or cellars untouched for many years. Sometimes they have been exposed to dust, dirt, water and who knows what else. An unfortunate colleague of mine recently opened a box of material. It had just been deposited with us after a very long time in an attic. Inside was a mouse’s nest, droppings, and the skeleton of the mouse itself.

Sometimes the dust and dirt can come not from the way the records were stored, but how they were used by their creators. Some industrial records betray signs of the factories they were used in, as we’ll see later. But although they (occasionally) arrive with us like that, archives certainly don’t stay that way. Dust and dirt can increase the speed at which archival materials decay, as well as providing an environment for pests which damage archives. Archivists and conservators spend a lot of time and effort making sure our archives are, and stay, clean.

The Moulton Family Papers Project

I recently worked on an Archives Revealed project to catalogue the papers of the Moulton family of Bradford on Avon, in Wiltshire. The family made its name working with Charles Goodyear to bring vulcanized rubber to the UK in the mid-1800s. Later Dr Alex Moulton went on to design the rubber suspension for the original Mini car in the late 1950s. The records had been stored in the cellar and attic of Dr Moulton’s seventeenth-century manor house, The Hall. This means that many of them were not in the cleanest of conditions.

Because of the damp atmosphere in the cellar, many of the old paperclips and other metal items had started to become corroded.

Corrosion causes staining and can eventually cause holes in paper. So oxidised fastenings are removed and replaced with brass paperclips, which are much more stable. This is quite a common problem, and solution, when dealing with archives. However sometimes the problems are more complex; sometimes the dirt tells a story of its own.

Many of the records from the family’s rubber business had been placed into storage in The Hall straight from the factory floor – literally, in some cases.

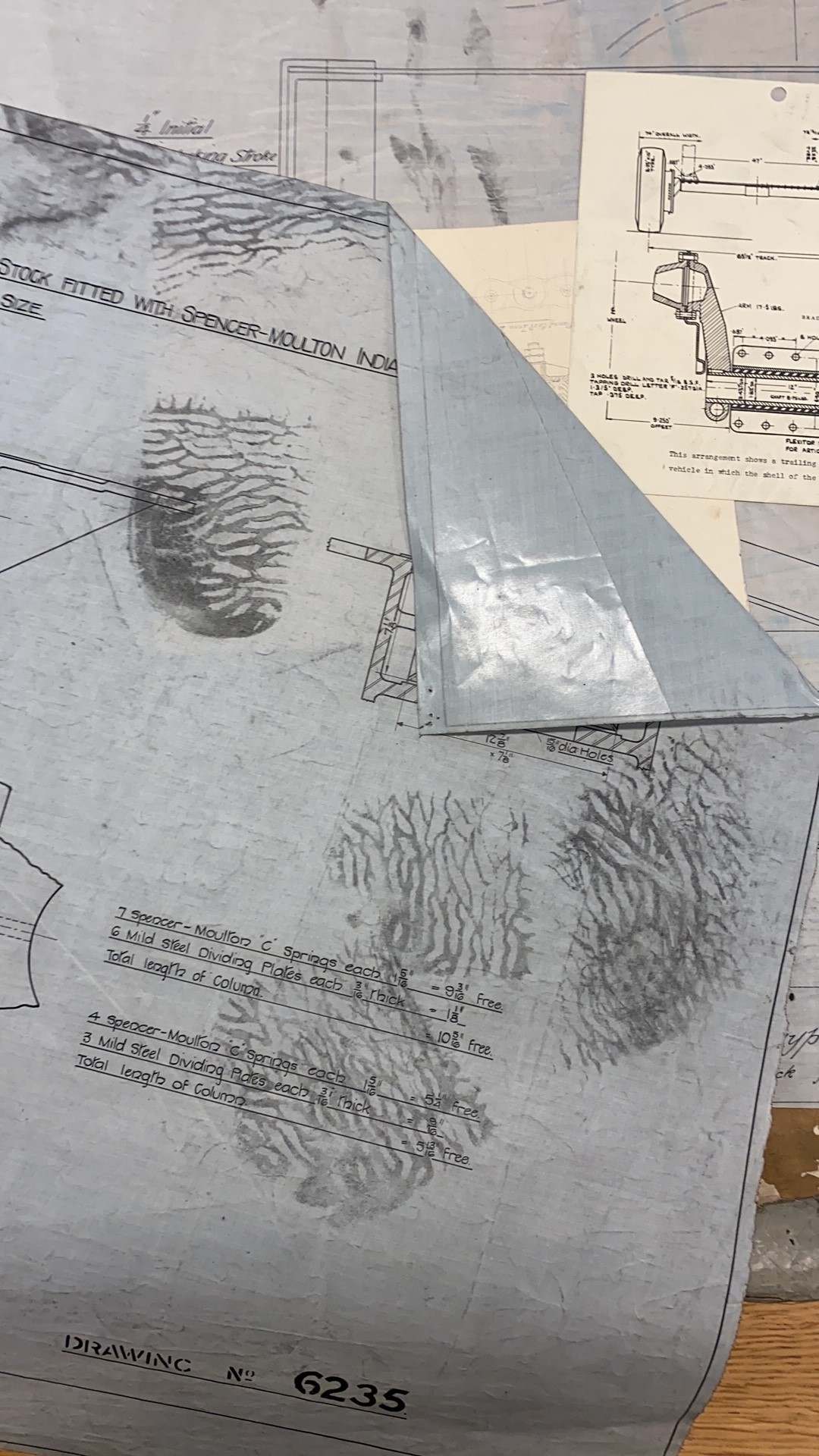

Trails from the past… perilous boot prints

Several of the firm’s technical drawings arrived with us showing very clear boot prints across their surface, almost certainly from their active life in the factory. Here, the dirt is both a problem and a source itself. It tells us about the life and usage of the document. It tells us perhaps as well about conditions in the rubber factory.

Unfortunately, the factory dirt was not quite so charming as the footprints first appear. Part of the rubber-making procedure included the addition of carbon black, or lamp black, as a pigment and reinforcing agent. Many of the earlier company records (potentially including the schematic shown above) were covered in residue from this process. Carbon black is potentially carcinogenic, so our archives conservator Sophie Coles is currently painstakingly cleaning each of the records in 180 boxes of material to make them safe for public use.

“The presence of potentially toxic dust from the rubber-making process was certainly an important factor in how the cleaning of the collection was approached.

It meant that the collection could not be handled, and boxes could not be opened by staff or volunteers until after cleaning had taken place.

Extra health and safety precautions had to be put in place when cleaning the documents including wearing a particular face mask and gloves whilst working in specially ventilated spaces known as fume cupboards. This was followed by careful decontamination of cleaning materials after use to avoid transfer of the dust.”

Sophie coles, conservator

Despite the admittedly rather unusual presence of carbon black in the Moulton collection, the removal of dust, dirt and other health hazards such as mould are extremely common issues.

Archivists and conservators face such problems when dealing with new deposits. Far from simply boxing the records up and leaving them to languish in this state, our work is as much about dustbusting as it is cataloguing.

Written by Tom Plant and Sophie Coles

Edited by Jake Doyle, Blog Coordinator for Explore Your Archive, MLitt Archives and Records Management Student and Archive Assistant at Suffolk Archives