What is secrecy? Writing this blog made me think about why archives created by some organisations are thought of as ‘secret’ whereas documentation created by others is considered more transparent. Data Protection and other information rights have transformed how restricted access periods are given to records. For various reasons certain records, once available for research, now have longer restricted access periods.

Archives and secrets

The Lord Chancellor’s advisory council ruled in 2004 that individuals’ records remain closed for 100 years from date of birth or until proof of death. Requests to access information held in records under Freedom of Information and related legislation need careful consideration. Archivists apply risk assessments and legislative guidelines on a case by case basis before providing information.

Researchers and archivists may remember the heady days, before the Freedom of Information Act changed everything in 2000, of the thirty year closure period for public records. Each year members of the press descended on The National Archives at Kew, keen to find secrets to expose in newly opened records. Since 2013, most public records are accessible after twenty years, unless access is limited based on damage to state security, foreign policy or personal privacy.

Access to information rules also apply to many museums or other bodies classed as public authorities under Freedom of Information legislation. Some businesses and organisations, such as the Museum of Freemasonry, are not public authorities. However, many welcome researchers to look at archives created or held on deposit in accordance with organisational access policies.

A new collection for the museum

In other cases, the creators or inheritors of resources may have expectations about access restrictions when records are deposited with an archive. This occurred when the Museum of Freemasonry acquired a private archive relating to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and its successor bodies. This collection, purchased in 2008 with the assistance of the Museums Libraries and Archives Council and the V&A Purchase Grant Fund, augmented material deposited in the 1920s by an individual.

Now catalogued with detailed item level descriptions the collection is proving popular with numerous researchers. You can find the entries on the Museum’s online catalogue (see below) and The National Archives’ Discovery catalogue. The Golden Dawn, which offered male and female membership, was founded by three freemasons, Dr William Wynn Westcott, Dr William Robert Woodman, and Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers in 1888. They were also members of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia (S.R.I.A.), which provides a natural home for philosophically inclined freemasons since 1867. SRIA members aim to work out life’s great problems through seeking intellectual and spiritual fulfilment.

The Order’s activities

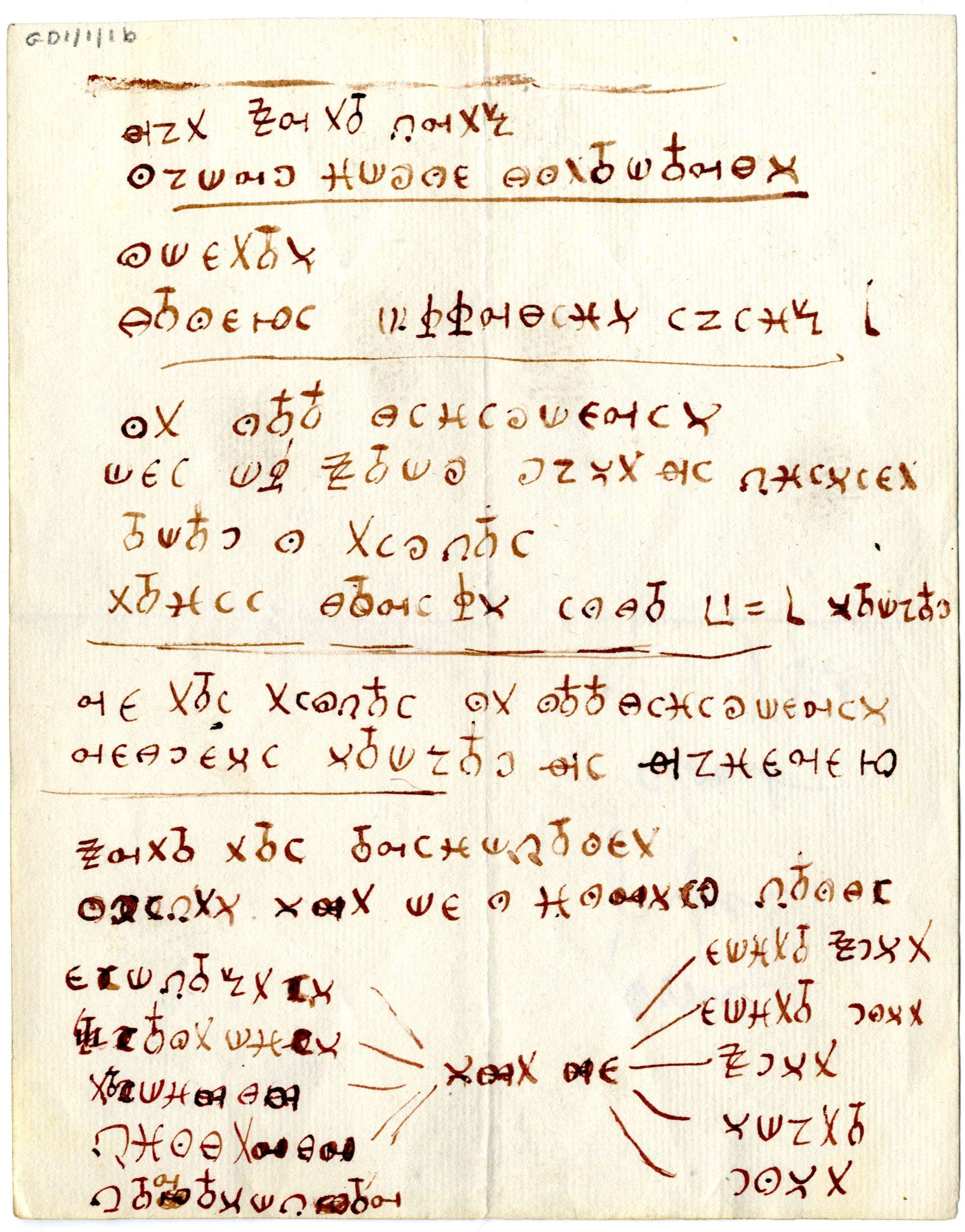

The Golden Dawn was based around rituals and knowledge lectures found in the Cipher Manuscripts, a series of encrypted documents containing outlines for a series of ‘secret’ initiation rituals. Order membership offered an attractive, sociable option before the days of radio and television for individuals interested in learning and inclined to contemplation. Members were encouraged to develop artistic skills and technical knowledge and to help with lectures on astronomy and philosophy. These were of particular interest to women with limited access to further education.

The rituals were encoded in cipher, enhancing their attraction as a source of hidden, ‘secret’ knowledge only accessible to a few through initiation. Papers found in the Cipher Manuscripts included an address for a German woman, Fräulein Sprengel, described as an Adept of an occult order known as the Die Goldene Dämmerung. Dr Westcott claimed she authorized him to set up a Temple in England with permission to sign her name. Some researchers believe Westcott created the Cipher Manuscripts to give the Golden Dawn a legitimate pedigree, which helped to attract serious occultists and freemasons to the new Order.

Orders within Orders

By the end of 1888 there were three Golden Dawn temples in London, Weston-Super-Mare and Bradford. At first functioning as a theoretical school, secret initiation ceremonies or grades were performed, covering the basics of Qabalah, astrology, alchemical symbolism, geomancy and tarot. No practical magic was performed until 1891, when Mathers compiled a ritual for an additional ‘secret’ Inner Order, known as the Order of the Rosae Rubeae et Aureae Crucis.

Mathers managed to reconstruct the Order after the death of Woodman, assuming a role as its primary Chief. Mathers and his artist wife, Moina (nee Mina Bergson) recreated an elaborate full-size version of the tomb of Christian Rosenkreuz, a legendary spiritualist. Known as the Vault of the Adepts, it was used to perform secret rituals by members of the Inner Order.

The archives of the Golden Dawn and successor bodies were rescued by former members and those attempting to work its secret rituals in the 1920s, after which time the Golden Dawn ceased to meet as a functional organisation. The Golden Dawn archive collection, which includes the Cipher Documents, is no longer secret and all items are available for research at the Museum of Freemasonry.

Further information

Catalogue of the Museum of Freemasonry: https://museumfreemasonry.org.uk/catalogue

Written by Susan Snell, Archivist and Records Manager at the Museum of Freemasonry, with many thanks to the Board of Trustees as well.

Edited by Isabel Lauterjung.