The importance of flora and fauna in the history & heritage of the Isle of Man.

As spring continues to blossom, and in celebration of Manx Wildlife week, we discover the life and works of naturalist William Cowin. We find out about his unique contribution to the field and a project using his works highlighting the island’s environmental changes.

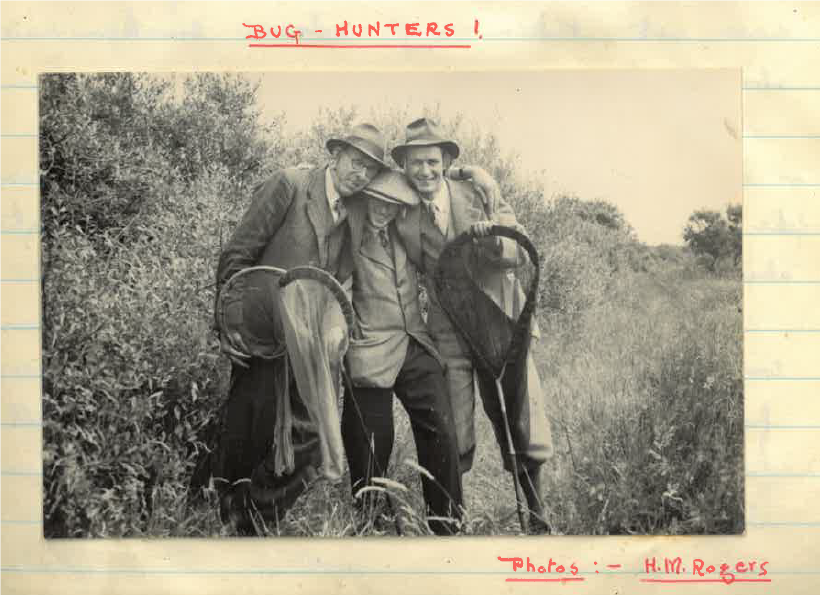

Naturalist William Stanley Cowin (1907-1958)

Co-founder of the Manx Field Club & Peregrine, a journal devoted to natural history.

William Cowin © Manx National Heritage (PG/7673)

Manx National Heritage Library and Archives are based at the Manx Museum in Douglas on the Isle of Man. They hold the 1935-1958 fieldwork diaries, all 16 volumes, of naturalist William Stanley Cowin. These are easily carriable and neatly handwritten. They represent an invaluable compendium of the local flora and fauna Cowin spotted on his excursions.

The diaries are the focus of a project rendering the information they contain, accessible to all. We can access their on the National Biodiversity Network Isle of Man website.

An Excellent Shot, a Gifted Naturalist and a Meticulous Recordkeeper

Born in the Isle of Man, William Cowin was an active field naturalist. As a schoolboy he kept meticulous records. The flowering dates of plants, the emergence of insects, and the birds that he saw were all recorded. Perhaps this reflected at some remove the influence of Philip Moore Callow Kermode, curator of the Manx Museum. Kermode did his best to foster an interest in wildlife among members of the Isle of Man Natural History and Antiquarian Society.

William Cowin was an excellent shot. He was also exempt form bird protection legislation to benefit the Manx Museum collection.

© Manx National Heritage (MS 09082/1)

William Cowin befriended the young Kenneth Williamson when he became museum assistant. Together they worked on the insects of the Island and started to form a new definitive voucher collection.

A Survey, a Publication and a Rare Find… William Cowin Discovers the Robber-Fly

They visited as often as they could the Calf of Man, a small island off the southern tip of the Isle of Man. They planned its future as a site for one of a chain of bird observatories on British shores (which it now is). Next they started on a systematic survey of the wildlife of Langness. In March 1938, they founded the Manx Field Club and published Peregrine. Their records and notes appeared in the journal North-Western Naturalist.

William achieved the difficult feat of finding an insect new to the British Isles and it was named in his honour, Epitriptus cowini. This robber-fly is now known as Machismus, but its epithet still honours this Manx naturalist.

Diary entry featuring notes about Cowin’s discovery of the robber-fly insect Epitriptus Cowini, now known as Machismus.

© Manx National Heritage (MS 09082/1)

William Cowin’s death came as a shock

Most particularly as he was engaged to be married. William’s natural history collections then became a valued part of the Manx Museum. His diaries were also later deposited in the Manx National Heritage Library and Archives (Reference number: MS 09082/1).

His fieldwork diaries cover the length and breadth of the Isle of Man and contain dated observations of what he saw. The locations can be tricky to pin-down (especially where different places have the same name). However a researcher will find with each diary a working familiarity. They can trace quite steadily Cowin’s movements in grid reference.

‘Cowin apparently disliked the combustion engine and instead went any distance he could by bicycle’ which makes it easier to conjure his route.

Jude dicken & laura mccoy

Tracking Environmental Changes Over Time – A New Transcription Project

Curator of the Manx National Heritage Laura McCoy is working with a volunteer to transcribe key contents of Cowin’s diaries. These ‘biological records’ are entries in the database (Recorder 6) and point-map data on the National Biodiversity Network website.

The importance of doing this, is having historical data allows you to track how our environment changes over time. Have there always been natural fluctuations and change, or is something drastically different? If a species starts dropping in numbers we can begin specific monitoring and find out why, and then hopefully help.

It is most valuable when we have a long time series of data, so the more consistent the recording the better.

laura mccoy

Further Information

Collections Information Manager, Jude Dicken

Natural History Curator, Laura McCoy

Edited by Jake Doyle, Blog Coordinator for Explore Your Archive, MLitt Archives and Records Management Student and Archive Assistant at Suffolk Archives